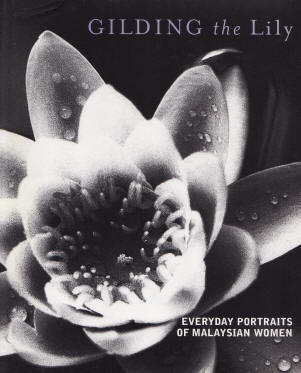

The following story is from

a book by Suet Fun and Shekar;

"Gilding The Lily".

The book contains 65 stories of individual Malaysian women and one story, "Everywhere"

is about Jeannie. I would like to thank the authors for the permission to

reproduce it here.

Incidentally, Jeannie loved white lilies and it

was her request to have the abundance of white lilies at her funeral.

Everywhere

She's everywhere. The cream

frilled curtains that fringe the doorway to the kitchen, the way the dining

table finds its cozy nook in the curve of the wall, the way the tea-lights burn,

night after night when they are lit to release the aromas from her favorite oils

and the way her scent lingers in the large wardrobe so that each time when the

doors are open, Jeannie's voice filters through, as though she is still there.

Her husband, Cheah Keat Swee, treads the fine line between feeling that she is

and isn't here anymore. I know she is gone, but she's still here, he says,

raising his hand and encircling the space in which she once lived and breathed.

Her face stares at you from above, in numerous photographs taken with the

family. She is impeccably dressed. She hated having her pictures taken in the

end, he says, because she had become so thin.

Jeannie had not been well for a long time. In more than twenty years of

marriage, she had undergone eleven major surgeries for various ailments and

caesarian sections, misdiagnosed with colon cancer and suffered from

endometriosis. Still, Cheah and Jeannie had two children, a girl and a boy named

Krystyn, now twenty and JJ, seventeen.

She fought everything for a long time, he says quietly. Her family background

was also wrought with challenges, and she had to leave home and fend for herself

at a very young age. WHEN CHEAH MET AND MARRIED JEANNIE, HE HAD "A BLUEPRINT TO

IMPROVE HER". HOW COULD I HAVE KNOWN THAT I WOULD BE THE ONE WHO WOULD BE

CHANGED, HE SAYS WONDERINGLY.

Cheah who was never brought up to be demonstrative learnt to speak of his

feelings. She demanded that I express myself, he says, and I think I loved her

so much, I wanted to do what was right. We always huddled together in the

bathroom, she on the floor with her cigarette and I on the toilet seat, with my

cigarette and we just talked, and talked.

For many years, her constant illnesses led Jeannie to have an impending sense of

her own death. She never mollycoddled her children and raised them to be

independent of her. Even from a young age, they were taught to get their own

breakfasts. She also had many conversations with Krystyn and JJ, speaking of

traditional values and behavior that was appropriate and expected of them. In

many ways, Krystyn says, she was preparing us to go on without her.

And now that the time has come, the road ahead seems too hard. Despite all the

careful prepping, the immense, inevitable sense of loss envelopes their home

like a thick, grey fog. Hope, he declares, has died.***

Now he sits, man alone, nursing a gin and tonic, taking a last draw from the

last stick of Virginia Slims, Jeannie's favorite cigarette, while Jeannie looks

down from above. And she is everywhere, but nowhere.

***

I had meant Jeannie's worldly hopes have

died with her. Our hopes with Jeannie have not died. Quite the contrary; hope is what

we are left with. (Keat, July 2008)